In 1959, as the Coachella Valley blossomed into a modernist playground, a unique structure rose from the dusty Indio landscape. This wasn’t just another desert home; it was a bold architectural statement destined to challenge conventions and inspire generations.

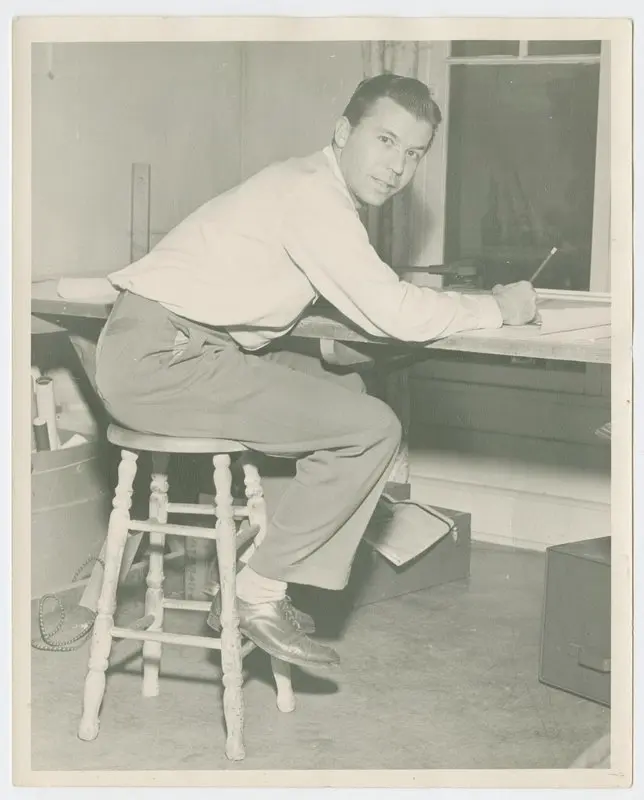

The mastermind behind this marvel was Walter S. White, a self-taught architect with a penchant for pushing boundaries. Born in 1917 in San Bernardino, White’s journey began in his father’s construction company, where he learned the nuts and bolts of building from the ground up. This practical experience would prove invaluable, giving him an edge that many formally trained architects lacked.

During World War II, White’s creative mind found a new outlet as a tool designer in an airplane factory, an experience that would later influence his innovative approach to architectural problems. Unlike many of his contemporaries, White never received formal architectural training. Instead, he learned by doing, working alongside some of the most influential architects of the mid-20th century.

In 1947, White returned to architecture, collaborating with Palm Springs luminaries John Porter Clark and Albert Frey. He also spent time in the offices of R.M. Schindler and Harwell Hamilton Harris, absorbing their modernist philosophies and innovative approaches. White’s time in the Coachella Valley, from 1948 to 1960, was a period of intense creativity and prolific output. He became a key figure in shaping Palm Desert’s architectural landscape, designing more than 50 houses across the desert in the 1940s and ’50s.

It was this rich background – a blend of practical construction knowledge, industrial design experience, and exposure to the brightest minds in modernist architecture – that White brought to the drawing board when Max Willcockson approached him in 1959. The result was nothing short of revolutionary.

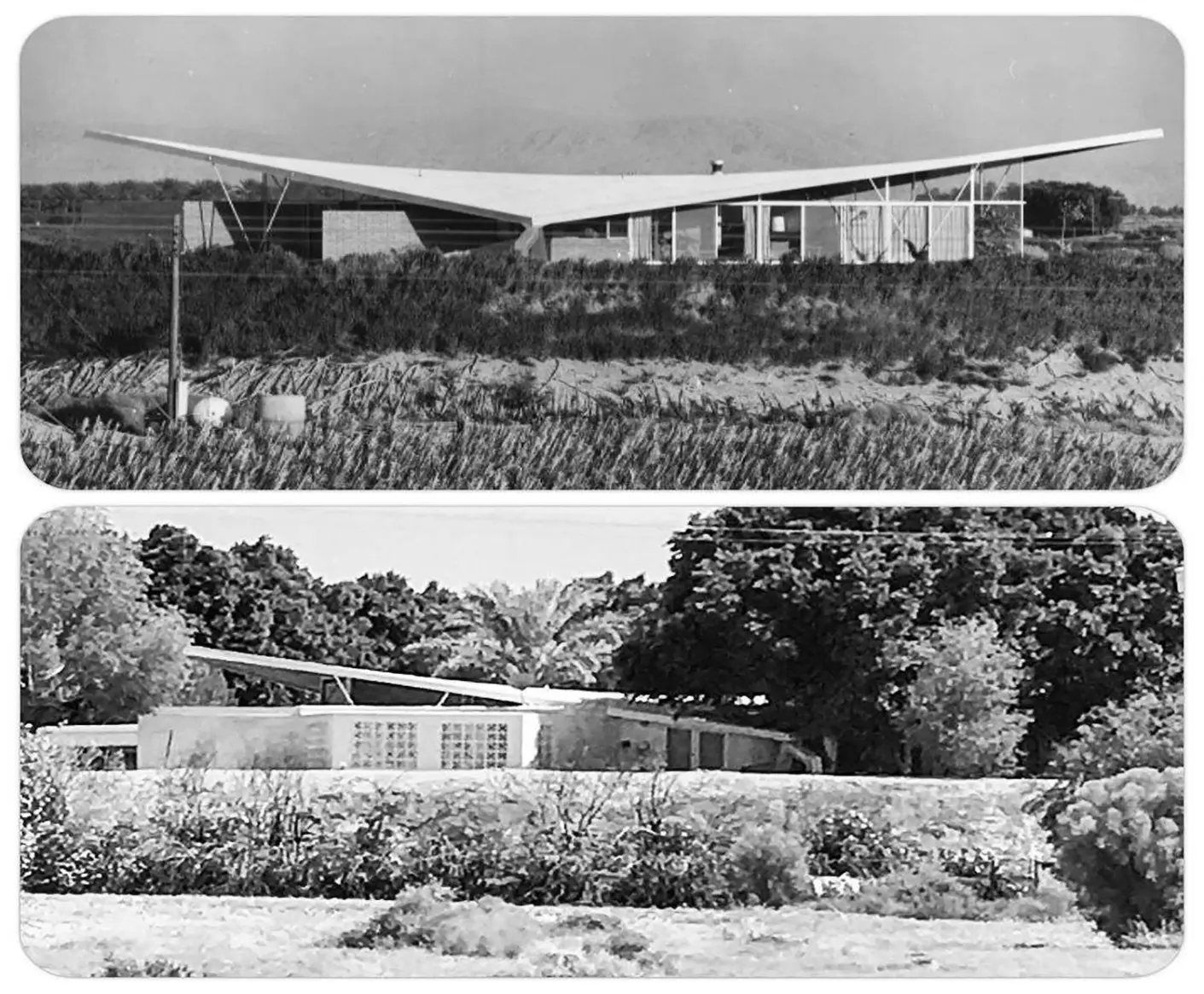

Perched atop a small bluff, the Willcockson house seemed to defy gravity. Its most striking feature, a hyperbolic paraboloid roof, appeared to float above the structure, supported by just two slender steel buttresses. This wasn’t just architectural showmanship; it was a feat of engineering that would influence desert modernism for years to come.

As news of this architectural wonder spread, the design world took notice. The prestigious Arts & Architecture magazine devoted a multi-page spread to the house, cementing its place in the annals of modernist design. But for Willcockson, it was simply home – a place where indoor and outdoor living blurred, where White’s ingenious design tamed the harsh desert sun, and where every sunrise and sunset became a spectacle framed by architectural brilliance.

Tragically, Willcockson’s time in his desert dream was cut short. He passed away just a few years after the home’s completion, leaving behind a legacy in steel and glass. But the house endured, a testament to one man’s vision and another’s genius.

Over the decades, the Desert White House has stood as a silent sentinel, weathering both literal and figurative storms, remaining a beacon of midcentury modern design amidst changing architectural trends. Today, as you approach the house, you’re not just visiting a home; you’re stepping into living history. The roof still seems to float impossibly above the desert floor, a reminder of White’s audacious vision. The open floor plan, made possible by the roof’s unique support system, continues to blur the lines between inside and out, just as it did over 60 years ago.

This isn’t just a house; it’s a story of innovation, a tale of two men who dared to dream big in the vast expanse of the California desert. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most extraordinary creations come from those who choose to color outside the lines.

As you stand in the shadow of this architectural marvel, you can almost hear echoes of the past – excited discussions between White and Willcockson, the buzz of the design world discovering this desert gem, and quiet moments of contemplation as Willcockson gazed out at the landscape from his floating oasis.

The Desert White House isn’t just preserved; it’s alive with history, ready to inspire the next generation of dreamers and innovators. It stands as a testament to the enduring power of bold ideas and the timeless appeal of desert modernism.

Photo credits: https://esotericsurvey.blogspot.com/ UCSB, Walter White, architect, “Walter White: Alexander house (Palm Springs, Calif.),” UCSB ADC Omeka, accessed November 4, 2021, http://www.adc-exhibits.museum.ucsb.edu/items/show/579. Image: UCSB Image: Arts & Architecture